Autonomy

The Monastery Series (Part 2)

In Part 1 of this series, I described how a Buddhist monastery in Vermont showed me a new worldview, one where Western values were flipped upside down.

This post will focus on one of those values: autonomy. Normally prized in the Western world, autonomy took on a new meaning at the monastery. After just two weeks, I left the monastery with a new perspective on how it contributes to a meaningful, happy life.

Autonomy

freedom from external control; independence

I crave autonomy in my daily life. It’s a huge part of why I place so much value on financial independence. It offers the freedom to decide how I spend my time, where I spend it, and who I spend it with. That has always, and still does, seem like a worthy goal and an important ingredient to happiness.

At the monastery, however, there was little autonomy. Daily schedules were packed and rigid. Tasks and responsibilities were predetermined. What you ate, who you lived with, and what you wore were chosen for you.

But, the residents were still happy. So, does that mean autonomy isn't essential for happiness?

Through my conversations with the people living there, I started to understand a new dimension of autonomy that I hadn’t considered before. Instead of “freedom from external control over my external circumstances,” it meant “freedom from external control over my state of mind.” Autonomy, in a monastic setting, comes from within.

During my stay, I learned that the rigid practice and style of Zen is meant to induce an inner freedom — an unshakable sense of ease and equanimity that is independent of external conditions. In the pressure cooker of that environment, where even your sitting posture is decided for you, you’re forced to transcend the desire for control and instead take ownership over your state of mind. If you can no longer find comfort in your hobbies, meals, entertainment, and leisure, then the mind becomes a place of refuge. It is, after all, the lens through which we experience the world.

With that said, I haven’t abandoned my original definition of autonomy. Having influence over how I spend my time is still important to me. But the monastery taught me that there’s another side to autonomy that’s just as important. True autonomy is being able to control both our circumstances and our state of mind.

The monastery also taught me that autonomy is like money: its value comes from exchanging it for something. At first, I thought that the residents had given up their autonomy, but I soon realized that they had actually traded it. They had decided that spiritual progress was important to them, so they traded their autonomy for daily instruction, group accountability, and a tight-knit community of like-minded peers. These three things are invaluable in any training environment, whether it’s a Buddhist monastery, a European soccer academy, or a military boot camp. They’re rocket fuel for progress.

Over the past few months, I’ve been taking a sabbatical from work, which means I’ve had more autonomy than ever. I’ve had the freedom to decide how I spend my time, where I spend it, and who I spend it with.

It’s been great and terrible. Great for the obvious reasons, but also terrible because it’s so damn hard to decide what to “spend” my autonomy on. My empty Google Calendar has become like an artist’s empty canvas — oppressively full of possibility. Should I work on that startup idea? Should I learn French or Muay Thai? Should I rent a cabin in the Pacific Northwest and hike and read for a few months? Should I fulfill that dream of visiting the world’s most beautiful libraries? Maybe I should just relax and unwind.

After three months, I’ve done none of those things. I have stories about why — perhaps if I had greater self-knowledge or conviction or guidance, I would have done them. But the main reason is that I’ve been treating autonomy like something to be preserved for its own sake. I’ve been so afraid to give up autonomy during my time off that I haven’t been willing to trade it, like someone who hoards money and then never ends up spending it.

The monastery showed me the error in this way of thinking. The real power of autonomy is being able to decide when to exchange it for something better.

So what is worth trading autonomy for?

I’m still trying to answer that for myself. But, in the meantime, I plan to start “spending” more of my autonomy and using it as a means for exploration. This newsletter has set a high bar. It’s been my only steady commitment during my time off, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything. It’s quickly become one of the most rewarding projects I’ve ever worked on.

New Definitions

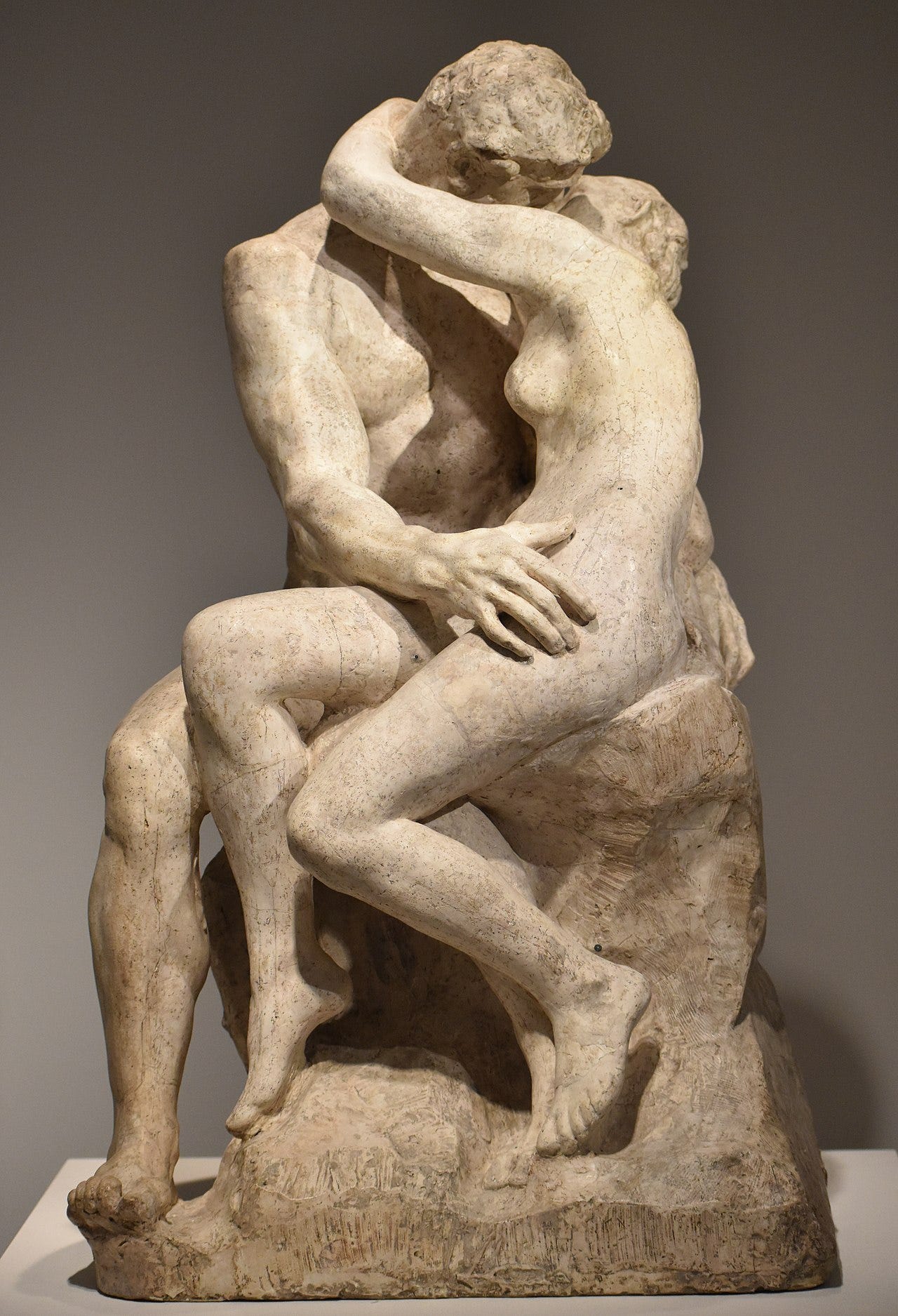

I’ll never forget my first visit to the Rodin Museum in Paris. Standing in front of The Kiss, I noticed the disappointment on our tour guide’s face. “No, no, no,” he said, tugging at my elbow, “when you look at a statue, you must not stay in the same place. You must walk around it and see it from every angle. There is always more than one story to be told.”

The monastery offered me the same lesson. Before my visit, I thought I had a firm grasp of the meaning of autonomy. But the monastery led me to see it from a new angle. Now I realize that there are dimensions that I hadn’t considered before — that it has more than one story, more than one definition.

I suppose that’s the gift of experiencing a new worldview. It may not replace our ideas, but it can reveal a new perspective that we had been missing.

As always, thanks for reading,

Mark

Often I am terrified of giving up autonomy. It's scary because autonomy gives a feeling--perhaps an illusion--of power. But for me, that power is not always satisfying. In fact, maybe never satisfying in itself. The true satisfaction comes from enacting, manifesting, and witnessing goodness, love, truth, justice, compassion, and joy. It's rare for me that those actually require power, and thus, autonomy. However, a lack of autonomy can sometimes force me to find new ways of doing good -- and that burden is scary. Likewise, signing up for trading away autonomy for something better requires trust and faith, that what is better will come to be.

I've been researching 12-step programs recently. The first step is admitting powerlessness over the addiction. The second, believing that a higher power has power over the addiction, and third, truly asking for it to use that power. The higher power can be interpreted in various ways, most often "God as I understand God," but even something like "my higher power is the 12-step group" is frequent. This process is often described in terms of surrender. Surrendering my will to God's, and trusting that God and the program really will heal my addiction. That might sound like the greatest possible sacrifice of autonomy. Yet, in exchange for that dependency, there is given a truer freedom -- freedom from addiction, freedom from inner compulsion, and freedom to be truly happy.

Hope you're doing well, Mark. Enjoyed reflecting on the post.

Wow, talk about a paradigm shift. Thanks for posting this, Mark! I'm also currently on sabbatical from work and I can relate to the difficulty of deciding what to “spend” your autonomy on.

This is a HUGE lightbulb moment: 'Instead of “freedom from external control over my external circumstances,” it meant “freedom from external control over my state of mind.” Autonomy, in a monastic setting, comes from within.'

And this! "The real power of autonomy is being able to decide when to exchange it for something better."

Have you written elsewhere about your time at the monastery in Vermont? I would love to read more about that experience.